La Pèira: A wine that speaks Occitan?

Around the time that Gaspard de Stérimberg, weary of slaughtering Cathars in Southern France, went off to retire and redecorate his small (now famous) abode on the Hermitage hill, the area where we work was still known as the Occitania.

The name simply meant the region (composed of a group of changing fiefdoms covering Southern France, Monaco, and parts of Italy and Spain) where the Language Occitan (or Òc) was spoken. Occitan was the first, and preferred, language of Richard the Lionheart, his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, and, most significantly, his Great Grandfather, William (Guilhem) IX, perhaps the first of the Occitan poets (Troubadours).

The poetry of the Troubadours, the dominant literary force in Europe from 1100–1350, in effect invented the idea of romantic love – then courtly love (as seen nowadays in countless Hollywood romantic comedies), Chivalry (if you’re struggling through Cervantes’ Don Quixote you know who to blame), and more fundamentally, instigated the move from writing in Classical Latin, to literature being written in the European romance languages that were actuality spoken on a day to day basis. To put this in perspective, at the time, the regional languages of Occitan, Italian, Spanish, and French were regarded a little like the various Vin de pays these days, whereas Classical Latin was the haughtiest of AOCs, out of the reach of most but regarded by all. But Occitan, a bit like Jazz in 1912, was breaking new ground, climbing up the charts…18 with a Bullet.

The Italians were spurred into action, as were the Trouveurs. Later Chaucer, impressed by the flourishing Serie A of medieval Italian poetry (and its top strikers) was among the first to kick off with a similar Premier League, writing in the vernacular English language rather than French or Latin. Let’s just say this, when Mistral (writing in Occitan) won the Nobel prize in 1904, let’s just hope he said, ‘First I’d like to thank the Troubadours’, and let’s hope no-one thought it was some new string quartet.

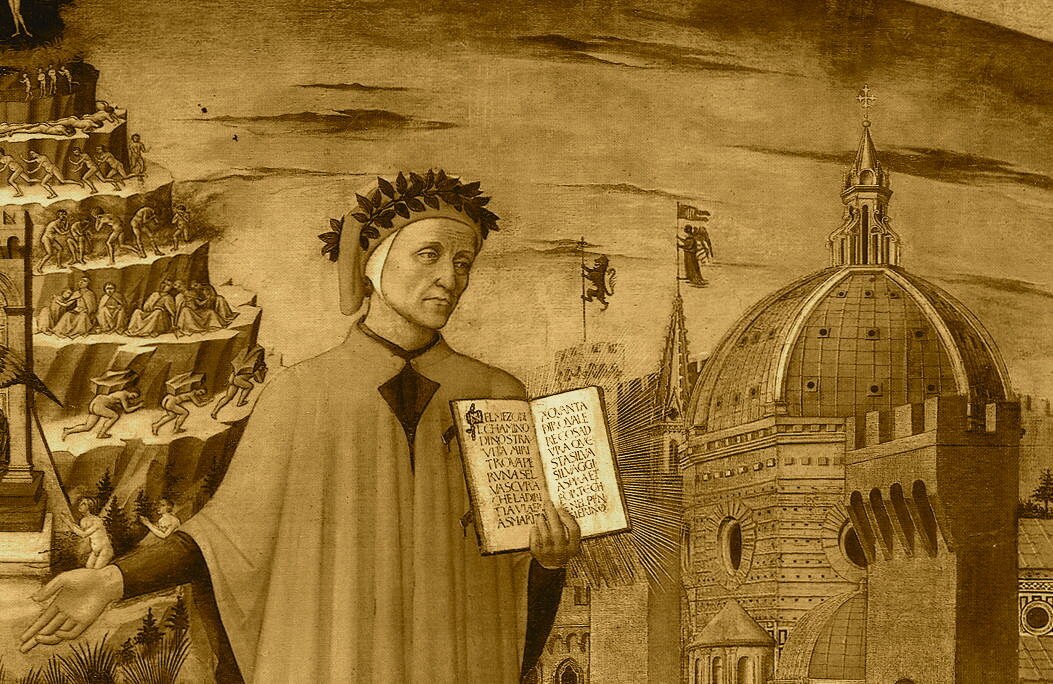

In 1210, Raimon Vidal de Bezaudun wrote Razos de trobar in which he asserted the superiority of Occitan over all other European vernaculars. This, in part, prompted Dante Alighieri’s De Vulgari Eloquentia (“Of Literature in the Vernacular”) essay on the historic evolution of language and the author’s search for an (indigenous) illustrious vernacular among the fourteen varieties he claimed to have found in the Italian region.In this work, he bemoans the popularity in Italy for composing and singing in Occitan, writing:

‘It is to the perpetual shame and sadness of the abominable Italians that they have taken command of another vernacular and despise their own.’

Dante differentiates between the three main romance languages of the time, the ‘Lingua d’Òc’ (Occitan), ‘Lingua di Sì’ (Italian), and ‘Lingua d’Oïl’ (Old French), noting that the language of Occitan (Òc) was particularly suited for poetry, while Old French (Oïl) was more suited to, “works of history and knowledge”, and citing the troubadour poet Peire d’Alvernhe.

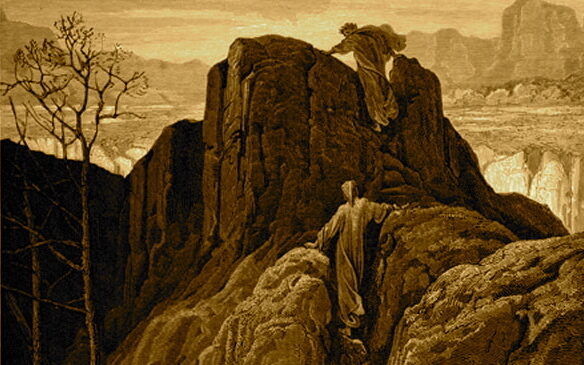

Dante’s wish to write in an Italian (or Tuscan) vernacular lead to his The Divine Comedy (Divina Commedia), which coincidentally happens to contain the most famous piece of Occitan ever set down on the printed page. On reaching Purgatory, Arnaut Danièl, (an Occitan troubadour of the 12th century praised by Dante as “il miglior fabbro del parlar materno” – the best craftsman of the mother tongue – and by Petrarch as the “gran maestro d’amor, ch’a la sua terra / ancor fa onor col suo dir strano e bello”– the grand master of love who still confers honor on his country through his strange and beautiful speech) appears as a character doing penance in Purgatory for lust. Prompted by the narrator as to his identity, he replies in Occitan:

“Tan m’abellis vostre cortes deman, / qu’ieu no me puesc ni voill a vos cobrire.

Ieu sui Arnaut, que plor e vau cantan; / consiros vei la passada folor,

e vei jausen lo joi qu’esper, denan. / Ara vos prec, per aquella valor

que vos guida al som de l’escalina, / sovenha vos a temps de ma dolor” (Purg., XXVI, 140-147)

Translation:

“Your courteous question pleases me so, / that I cannot and will not hide from you.

I am Arnaut, who weeping and singing go; / Contrite I see the folly of the past,

And, joyous, I foresee the joy I hope for one day. / Therefore do I implore you, by that power /

Which guides you to the summit of the stairs, / Remember my suffering, in the right time.”

In 1258, the Languedoc was officially ceded to the Kings of France. And so at the time the largest and richest province of what we now know as France (Dante called Languedoc ‘the great Provençal dowry’) found a new political master. This change in political control was small beer to a region that had seen so many. Yet from this point on…well let’s leave it to Britannica to note: ‘the Occitan was rich in poetic literature in the Middle Ages until the north crushed political power in the south (1208–29).’

The region remained a vibrant one. Still is today. In 1573, Spanish rabbi Benjamin of Tudela described Occitania as a marketplace bringing together “Christians and Muslims, where Arabs, Lombard merchants, visitors from Rome, from all parts of Egypt, the lands of Israel, Greece, Gaul, Genoa, and Pisa. All languages are spoken there”.

Today, Michelin-starred chefs such as the Heston Blumenthal of the Fat Duck fondly reminisce about discovering the region’s greatest wines. Publications such as the Lonely Planet note, ‘this Cinderella of the south was once overshadowed by gorgeous Provence and the brash Côte d’Azur. Now, she stands as their equal, displaying a discreet charm that her more-visited siblings lost long ago’, in their worldwide hot list of 2009.

Innovative sites classify the region’s churches, towns, beaches, regions, sites, and produce, and others such as Gemma Crangle’s Terroir Languedoc, deal exclusively in its wines. Tabloids in England publish articles, no doubt prompted by the two hour travel time, as do Broadsheets such as The Independent, The Times, and The Telegraph. Hotels such as Le Couvent d’Herepian, and le Clos de Maussanne, the new Lodge St Germain, and the Le Jardin des Sens cater for every whim.

But a Land that cannot recognise its riches in one field, cannot do so in another, and amazingly, Occitan is regarded in France (wrongly if the world’s linguistic experts are correct) as a Patois. Imagine Tuscany without Italian, Priorat without Catalan, or even Kansas without Dorothy, and you have the Languedoc without Occitan. A land where the indigenous language is something to be hidden, and not something to be celebrated.

How can a wine express a unique voice, if the language of those who have tended to its soils for centuries is left disregarded?

And so we search on in the Terrasses du Larzac, for a regional and ‘illustrious vernacular’, that in time may take its place among the treasures of France. Boats against the current, maybe. Worthy of exploration, of course.

Join La Peira on: Twitter | Facebook | Linkedin | Friendfeed | Flickr | Disqus